The John Thornton Young Achievers Foundation (JTYAF) supports young people in a wide range of youth organisations and provides them with scholarships to support their personal development and the pursuit of their ambitions. It was established following the death of my younger brother, John, on active service in Afghanistan in 2008. John, a Royal Marines officer, achieved an incredible amount in his short life and so the provision of opportunities for young people to live their dreams, like he was able to do, seemed the perfect way to honour such an inspirational person. Since its formation we have made awards totaling nearly £250,000 to over 550 young people. A legacy that John would be both amazed by and proud of.

The John Thornton Young Achievers Foundation (JTYAF) supports young people in a wide range of youth organisations and provides them with scholarships to support their personal development and the pursuit of their ambitions. It was established following the death of my younger brother, John, on active service in Afghanistan in 2008. John, a Royal Marines officer, achieved an incredible amount in his short life and so the provision of opportunities for young people to live their dreams, like he was able to do, seemed the perfect way to honour such an inspirational person. Since its formation we have made awards totaling nearly £250,000 to over 550 young people. A legacy that John would be both amazed by and proud of.

There are a wide variety of ways in which people can help or contribute. We have an amazing network of volunteers, without whose help our numerous fundraising events wouldn’t get off the ground. The amount of people who have also helped through organising sponsored events is also overwhelming; from tea parties in local care homes to successfully summiting Mount Everest, our supporters have completely blown us away with their imagination, commitment and passion for this cause. People can also simply donate via our website www.jtyaf.org, or can follow links to fundraising webpages set up by those who are supporting us. Every penny truly helps and, with no premises to fund or paid staff to take into account, very nearly all of every pound donated goes directly towards the young people that we provide opportunities for.

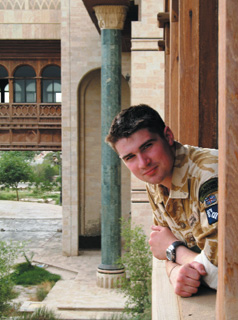

The JTYAF certainly does keep the spirit of John alive. By the age of 22 he had climbed Mount Kilimanjaro, flown with the Red Arrows, qualified as a free-fall skydiver, travelled across New Zealand, learnt musical instruments and played a wide variety of sports, and had worked in both Iraq and Afghanistan as a Royal Marines officer. He achieved more in such a short space of time than many do by the time they reach old age, and being able to help others realise their ambitions and conquer their own personal challenges is so fitting. The sheer scale of the support we receive really is testament to the uniquely inspirational person that John was more than anything else.

Putting together “Helmand” was hard in that it revisited a truly traumatic moment in my life in it’s references to my brother’s death. That said, it was also a therapeutic experience as it gave me the opportunity to look in detail at how he spent the final weeks and months of his life, and to learn about how his experiences fitted in with those of the Officers and Marines that he was deployed alongside. Including my own diary of my time in Afghanistan, some 4.5 years later, was something I was not initially comfortable with as I only ever wrote for my own benefit and to keep a record of everything that my Platoon and I went through together. It was never meant for anyone else’s eyes. However, in hindsight, to have the opportunity to hopefully do justice to the experiences of the soldiers I fought alongside is both rare and an honour, and at the same time I think the ability to contrast my tour with that of John gives the reader a true sense of the incredible progress that was made by the British Armed Forces in Afghanistan in those few short years.

I would like to write another book at some point in the future, but think that it may have to wait until my career in the Army has ended…I doubt I’d have the time to do so until then!

It’s difficult to say whether or not military personnel get the treatment they deserve on returning to civilian life as I am yet to make that jump. I certainly hope that they do. I think that the public perception of the Armed Forces is the most positive it has been for a long time, due largely to a respect for our sacrifices in Iraq and Afghanistan, and I hope that this manifests itself in the upholding of the military covenant for those who make the big decision to return to civilian life.

When I deployed to Afghanistan I felt so many emotions. In the time leading up to deployment excitement gradually gave way to apprehension about the unknown and ultimately a sense of fear prior to stepping out of the gate on patrol that first time. That fear however was not of personally dying or being injured as, ultimately, your training gets you so used to the idea of both that you kind of expect it to happen. The fear that I felt was of letting those around me down, and of what it would do to my family if the worst would have happened again. Letting people down is something on the mind of, I believe, everyone experiencing combat for the first time. Until you have been shot at for the first time you have literally no idea about how you will react. For me personally, the fear of putting my family through another loss so soon after we lost John was something that was on my mind constantly. I know that both of my parents struggled with me being away and spent the entire 6 months hoping and praying that lighting wouldn’t strike twice. To me though they were so supportive – despite their fears they knew that it was the only thing I wanted to do and as my Mum said, “as a parent all you want is for your children to be happy”. Before I deployed I remember saying: “Mum, this is my World Cup”. I wanted to make sure that if the worst did happen, she would know that my time came when I was doing something that I loved.

The best advice I have ever been given came from John, which was simply: “Don’t worry, everything will turn out for the best – because it always does”. I think that’s a good outlook to have on life.