With writing, there’s always a spark that ignites the flame. In my case, it was a small grey plaque almost hidden inside the entrance to a school.

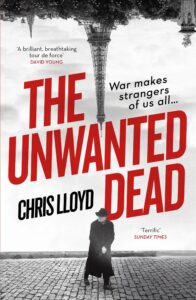

But I’m getting ahead of myself. My name’s Chris Lloyd and I write crime fiction. I’m from Wales, but I studied Spanish and French at university and fell head over heels in love with the Catalan city of Girona when I spent my study year there. So much so that after I graduated, I hopped straight on the first bus back to Catalonia and there I stayed for nearly a quarter of a century.

I taught English in Girona for a few years before moving to Bilbao, in the Basque Country, where I opened the Oxford University Press office. After that, I moved back to Catalonia – specifically to Barcelona – where I lived for the next sixteen years, apart from a three-year stint in Madrid. I also spent a semester in Grenoble, where I researched the French Resistance movement – you’ll discover the reason for that in a moment.

I taught English in Girona for a few years before moving to Bilbao, in the Basque Country, where I opened the Oxford University Press office. After that, I moved back to Catalonia – specifically to Barcelona – where I lived for the next sixteen years, apart from a three-year stint in Madrid. I also spent a semester in Grenoble, where I researched the French Resistance movement – you’ll discover the reason for that in a moment.

My job in educational publishing meant that I was paid to travel all around Spain giving workshops and book presentations, which was great fun until it stopped being great fun. That’s when I took voluntary redundancy three days before my fortieth birthday and set up as a Catalan and Spanish translator. I also wrote travel books for Rough Guides at the same time, until my wife and I decided it was time to move to Wales, which is where we live now, in the town where I grew up. All good stories should come full circle.

Which brings me back to the spark.

It was a small grey plaque in a nondescript building and it stopped me in my tracks. It was in the Pletzel, a district of Paris that was home to much of the city’s Jewish population in 1940, and it listed the children from the school who had been sent to Auschwitz and never returned.

I was already researching for a novel set in the city under the Occupation – my fascination with the era and the oddly blurred notions of resistance and collaboration had been ignited when I was in Grenoble – but it was that moment when I felt the small hand of history tug at my sleeve and I knew that I had to tell the story of the city under the Nazis as truthfully as possible.

But I had to tell it my way, through crime fiction. About a Paris police detective, Eddie Giral, a veteran of the last war, who struggles to do his job and retain a moral compass under the new rules imposed on the city and the people. On the day the Nazis enter the city, four Polish refugees are found gassed in a railway truck, and only Eddie among the police feels the need to find out the truth of what happened to them. This will lead him into conflict with his fellow police, an American journalist, the Polish Resistance and, most dangerously of all, the Occupiers. It will also lead him to question decisions he made in the past and decide what he must do to atone in the present.

But I had to tell it my way, through crime fiction. About a Paris police detective, Eddie Giral, a veteran of the last war, who struggles to do his job and retain a moral compass under the new rules imposed on the city and the people. On the day the Nazis enter the city, four Polish refugees are found gassed in a railway truck, and only Eddie among the police feels the need to find out the truth of what happened to them. This will lead him into conflict with his fellow police, an American journalist, the Polish Resistance and, most dangerously of all, the Occupiers. It will also lead him to question decisions he made in the past and decide what he must do to atone in the present.

The first book in the series, The Unwanted Dead, recently won the HWA Gold Crown Award and was shortlisted for the CWA Historical Dagger. The second book, Paris Requiem, comes out in 2022, and I’m currently writing the third in the series, set at Christmas 1940, although with little seasonal cheer or goodwill.

On which note, please allow me to wish you all the very best of cheer for Christmas and the year ahead. And lots of good books to enjoy.

Read more about Chris at https://chrislloydauthor.com/