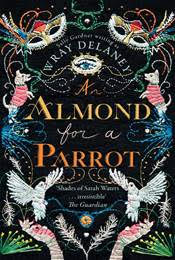

Frost loved Sally Gardner’s first adult novel, An Almond for a Parrot so we are very excited to bring you an extract. An Almond for a Parrot follows London’s most famous courtesan, Tully Truegood, from her childhood of neglect in the 18th Century London to an upper-class brothel where decadent excess is a must. Now she is awaiting trial for murder, for which she expects to hang. This is her truth, a letter written to the man she has loved and fears lost…

Frost loved Sally Gardner’s first adult novel, An Almond for a Parrot so we are very excited to bring you an extract. An Almond for a Parrot follows London’s most famous courtesan, Tully Truegood, from her childhood of neglect in the 18th Century London to an upper-class brothel where decadent excess is a must. Now she is awaiting trial for murder, for which she expects to hang. This is her truth, a letter written to the man she has loved and fears lost…

Chapter One

Newgate Prison, London

I lie on this hard bed counting the bricks in the ceiling of this miserable cell. I have been sick every morning for a week and thought I might have jail fever. If it had killed me it would at least have saved me the inconvenience of a trial and a public hanging. Already the best seats at Newgate Prison have been sold in anticipation of my being found guilty – and I have yet to be sent to trial. Murder, attempted murder – either way the great metropolis seems to know the verdict before the judge has placed the black square on his grey wig. This whore is gallows-bound.

‘Is he dead?’ I asked.

My jailer wouldn’t say.

I pass my days remembering recipes and reciting them to the damp walls. They don’t remind me of food; they are bookmarks from this short life of mine. They remain tasteless. I prefer them that way.

A doctor was called for. Who sent for or paid for him I don’t know, and uncharacteristically I do not care. He was very matter of fact and said the reason for my malady was simple: I was with child. I haven’t laughed for a long time but forgive me, the thought struck me as ridiculous. In all that has happened I have never once found myself in this predicament. I can hardly

believe it is true. The doctor looked relieved – he had at least found a reason for my life to be extended – pregnant women are not hanged. Even if I’m found guilty of murder, the gallows will wait until the child is born. What a comforting thought.

Hope came shortly afterwards. Dear Hope. She looked worried, thinner.

‘How is Mercy?’ I asked.

She avoided answering me and busied herself about my cell. ‘What does this mean?’ she asked, running her fingers over the words scratched on a small table, the only piece of furniture this stinking cell has to offer.

I had spent some time etching them into its worm-eaten surface. An Almond for a Parrot.

‘It’s a title for a memoir, the unanswered love song of a soon- to-be dead bird. Except I have no paper, no pen and without ink the thing won’t write at all.’

‘Just as well, Tully.’

‘I want to tell the truth of my life.’

‘Better to leave it,’ she said.

‘It’s for Avery – not that he will ever read it.’ I felt myself on the brink of tears but I refused to give in to them. ‘I will write it for myself. Afterwards, it can be your bedtime entertainment, the novelty of my days in recipes and tittle-tattle.’

‘Oh, my sweet ninny-not. You must be brave, Tully. This is a dreadful place and…’

‘And it is not my first prison. My life has come full circle. You haven’t answered my question.’

‘Mercy is still very ill. Mofty is with her.’ ‘Will she live?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘And is he alive?’

‘Tully, he is dead. You are to be tried for murder.’

‘My, oh my. At least my aim was true.’

I sank back on the bed, too tired to ask more. Even if Hope was in the mood for answering questions, I didn’t think I would want to know the answers.

‘You are a celebrity in London. Everyone wants to know what you do, what you wear. The papers are full of it.’

There seemed nothing to say to that. Hope sat quietly on the edge of the bed, holding my hand.

Finally, I found the courage to ask the question I’d wanted to ask since Hope arrived.

‘Is there any news of Avery?’

‘No, Tully, there’s not.’

I shook my head. Regret. I am full of it. A stone to worry one’s soul with.

‘You have done nothing wrong, Tully.’

‘Forgive me for laughing.’

‘You will have the very best solicitor.’

‘Who will pay for him?’

‘Queenie.’

‘No, no. I don’t want her to. I have some jewels…’ I felt sick.

‘Concentrate on staying well,’ said Hope.

If this life was a dress rehearsal, I would now have a chance to play my part again but with a more favourable outcome. Alas, we players are unaware that the curtain goes up the minute we take our first gulps of air; the screams of rage our only hopeless comments on being born onto such a barren stage.

So here I am with ink, pen and a box of writing paper, courtesy of a well-wisher. Still I wait to know the date of my trial. What to do until then? Write, Tully, write.

With a hey ho the wind and the rain. And words are my only escape. For the rain it raineth every day.

Available from amazon.co.uk and waterstones.com