What you have written, past and present

What you have written, past and present

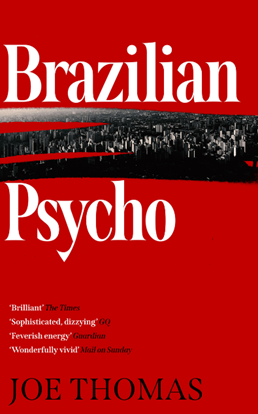

I am the author of a quartet of standalone but connected novels set in São Paulo, where I lived for ten years – Paradise City, Gringa, Playboy, and Brazilian Psycho. I have also published Bent, a historical crime novel set in Soho in the 1960’s and behind the lines in Italy during the Second World War, based on the life of war hero and notorious detective Harold ‘Tanky’ Challenor, who was in the SAS with my grandfather.

What you are promoting now

My latest novel, Brazilian Psycho, is an occult history of the city of São Paulo from 2003 – 2019, told through the lens of real-life crimes. It reveals the dark heart at the centre of the Brazilian social-democrat resurgence and the fragility and corruption of the B.R.I.C economic miracle; it documents the rise and fall of the left-wing – and the rise of the populist right.

The novel features the chaos and score-settling of the PCC drug gang rebellion over Mothers’ Day weekend, 2006; the murder of a British school headmaster and the consequent cover-up; a copycat serial killer; the secret international funding of nationwide anti-government protests; the bribes, kickbacks and shakedowns of the Mensalão and Lava Jato political corruption scandals.

A bit about your process of writing

I am a crime novelist interested in fiction based on fact, inspired by true stories of structural inequality. My fiction addresses the discourses of power and the specificity of crime, why something happened precisely where it did, and is an attempt to illuminate the reasons why.

I tend to plan my novels loosely and read a good deal before beginning the writing. Once I have a defined structure, then I write in earnest. At this point, I will research, plan, and write at the same time. What this means is that I write one section of a novel and read around the section that follows. I find that this keeps everything fresh!

In terms of structure, I tend to think in units of time, so do I want each chapter or section to cover a day, a week, six months, etc. As so much of what I write is based on reality, these units of time are often defined for me; I simply follow what happened and when! I find this both an anchor and liberating, too, in terms of having that tightly defined framework to exploit fictionally.

I want to be thought of as a writer pushing the form and writing political, meaningful, literary crime fiction. My goal is to build a body of work and I am very lucky to have the opportunity to do just that.

What about word count?

I have a very irritating habit: whenever I stop writing, or even pause for a moment, the word count has to end in either zero or five. I will tinker with sentences for this to be the case! In some ways it helps with editing; in others it is likely counter-productive!

What do you find hard about writing?

Having to overcome my own irritating habits! I used to think that I had to write first thing in the morning to produce anything of quality; since having a son – who is now twenty-months old – I am learning to use any part of the day I can. This is not always easy!

What do you love about writing?

I love that the days when I do it feel better than the days when I don’t.

Brazilian Psycho by Joe Thomas is out now in hardback by Arcadia.