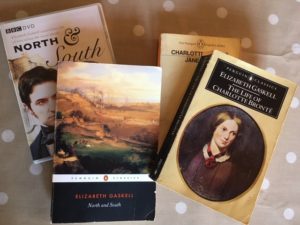

The other day, I had the urge to watch North & South again, the well-received BBC dramatization of Elizabeth Gaskell’s second novel.

I’m not sure if this stemmed from a need to watch a classic film or simply the shallowness of wanting to wallow in Richard Armitage’s smouldering interpretation of John Thornton, but whatever the attraction, it did make me think about Victorian writers.

Written originally for Charles Dickens’ magazine, Household Words, North & South has more recently been dubbed the ‘industrial’ Pride & Prejudice. It is typical of the stories spilling from Mrs Gaskell’s pen at this time: ones that didn’t flinch away from contentious social commentary but always had, at their heart, a bit of romance – and a copious body count!

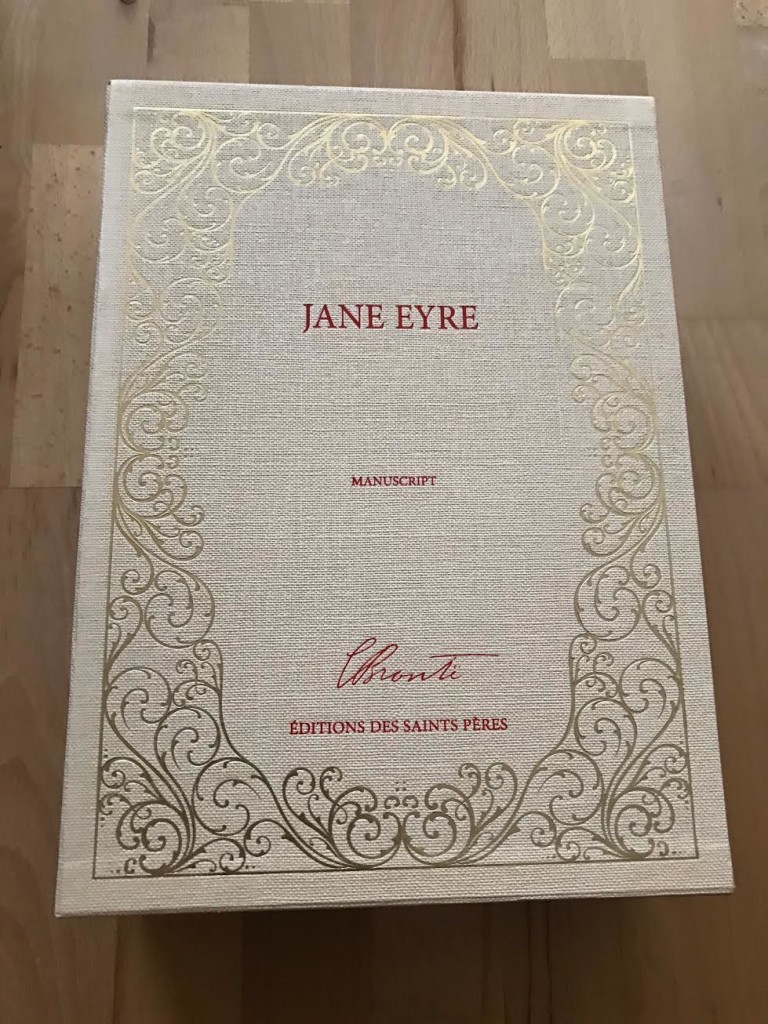

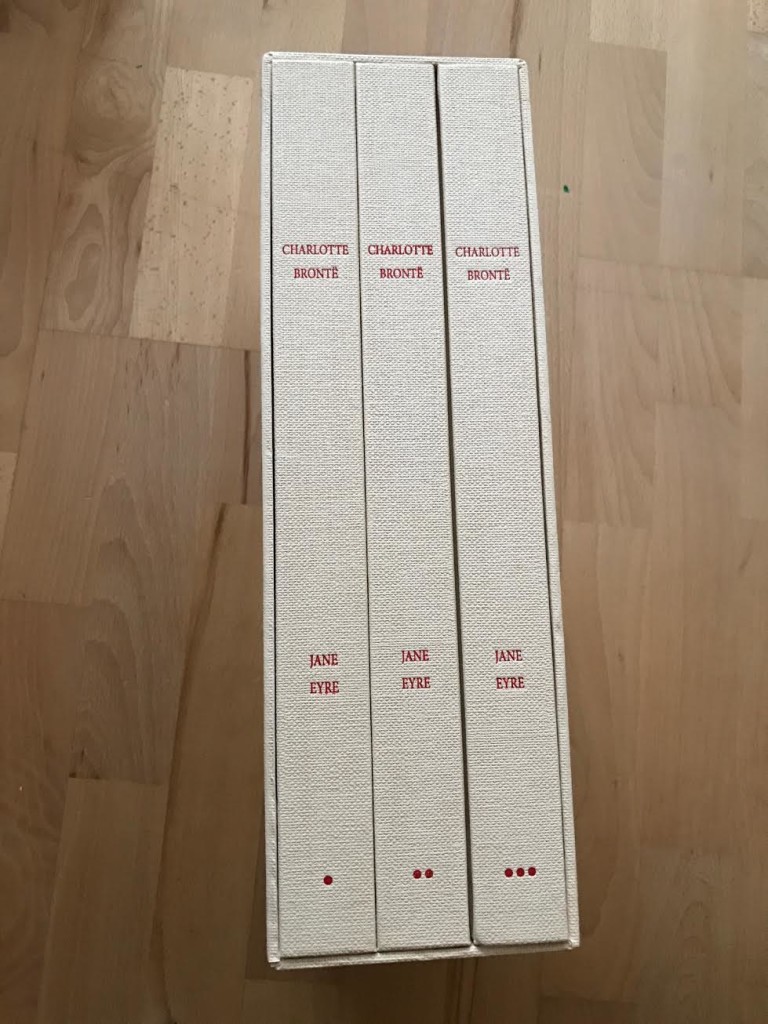

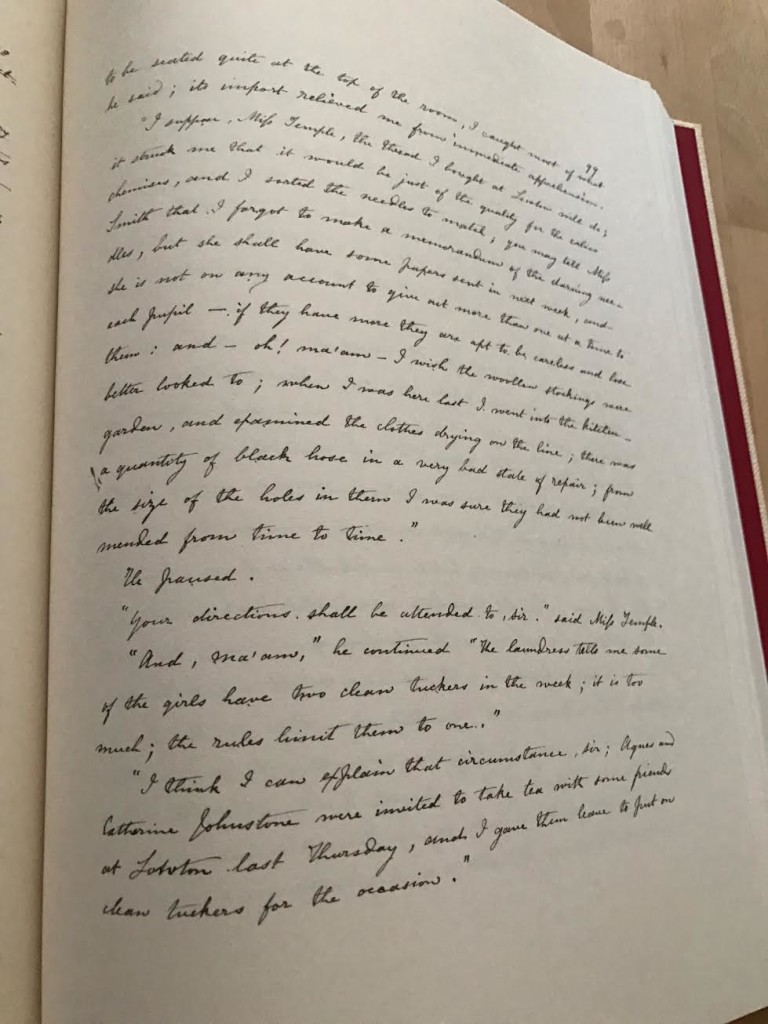

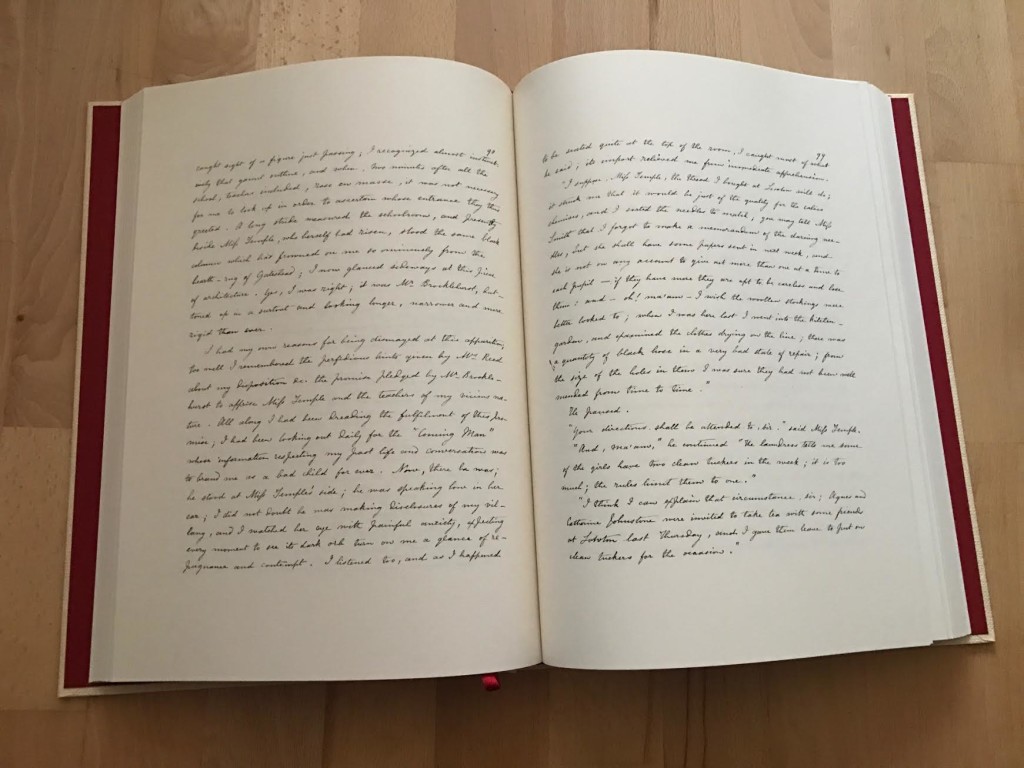

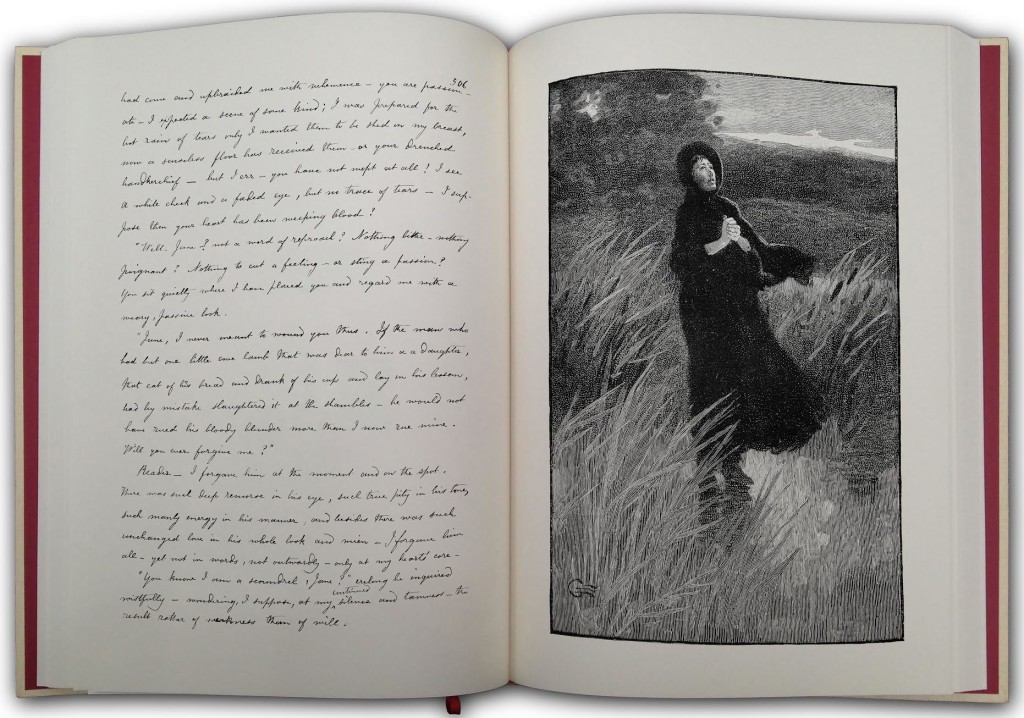

It wasn’t a novel, however, that first introduced me to Mrs Gaskell’s writing. Back in school, I was obliged to read Jane Eyre as a set book. My teenage heart was swept away by the passion of Charlotte Brontë’s classic and, considering myself plain and unnoticeable, I relished reading about this ‘oh so ordinary’ heroine getting her man.

Intrigued by the story behind the author, I bought a copy of a popular biography of Charlotte – the aforementioned Mrs Gaskell’s account of ‘The Life of Charlotte Brontë, having no idea of the drama surrounding the book.

It was written at the invitation of Charlotte’s father soon after his daughter’s death in 1855. Encouraged by Charlotte’s close friend, Ellen Nussey, Patrick Brontë wanted Mrs Gaskell, also a friend of his daughter’s, “to publish a long or short account of her life and works, just as you deem expedient and proper”.

Mrs Gaskell was used to her own writing exciting controversy amidst the admiration, but although the biography attracted critical acclaim, it was not universally well-received, with some critics not appreciating the whitewashing of certain aspects of Charlotte’s life. Mrs Gaskell had been stuck between the proverbial rock and a hard place – after all, parts of Charlotte’s life (like anyone’s) were not really for public consumption.

More controversy, however, came back to haunt the author. Published in March 1857, the Life attracted enough attention for a second edition to be announced in May of the same year. Suddenly, though, the book was withdrawn from sale, due to the threat of libel proceedings on more than one count and general grumblings from those who felt they had been unfairly depicted in the book.

More controversy, however, came back to haunt the author. Published in March 1857, the Life attracted enough attention for a second edition to be announced in May of the same year. Suddenly, though, the book was withdrawn from sale, due to the threat of libel proceedings on more than one count and general grumblings from those who felt they had been unfairly depicted in the book.

The three main issues seem to have been these: how Patrick Brontë himself was portrayed; the account of Charlotte’s brother, Branwell’s, decline – exacerbated by the implication of the influence of a ‘lady’, who was described in such a way, all of society knew her identity; and descriptions of Charlotte and her sister, Emily’s, time at the Clergy Daughters’ School at Cowan Bridge.

Mrs Gaskell went on to describe herself as being in ‘the hornet’s nest with a vengeance’ and referred to the biography as ‘this unlucky book’ in a letter to her publisher. Its overall success, however, meant the Life wasn’t going to disappear. Balancing out the unpleasantness of the above, Mrs Gaskell began to receive additional information, either from others who admired what she had already achieved or those who wanted to correct certain details.

She faced a daunting major revision, but set to and the third edition – Revised and Corrected – appeared in the November, less than six months after the original had been withdrawn from sale. It contained a substantial amount of new material.

Despite the challenges she faced, Elizabeth Gaskell did an admirable job, and her insight into the life of Charlotte Brontë is a fascinating read and one I would highly recommend to anyone who enjoys reading about Victorian authors.

As for myself, I think I’ll avoid any attempts to pen biographies for my writing friends and immerse myself in fiction instead – the visual rather than the written version on this occasion! Excuse me whilst I hit play again on North & South… I may be gone some time!

Sources: Various Gaskell letters, and Alan Shelston’s Introduction and Appendices to the Penguin English Library 1975 edition of Jane Eyre