The UK Cancer Drug Fund, which funds non-NHS cancer treatments, has removed twenty-five drugs off its list recently, to combat a £100 million (and rising) overspend. This highlights a recurring dilemma of modern healthcare.

Medical science is advancing with cosmic speed. Patients with desperate diseases have new hope. Genetic advances allow personalised medicine for enhanced individual benefit.

However, drug costs are becoming frighteningly high, and, as people live longer, health budgets rise further. To be cynical, it was cheaper when people simply didn’t survive.

In response, many governments have attempted to force medicine prices down. Politically a quick win. But what are the consequences?

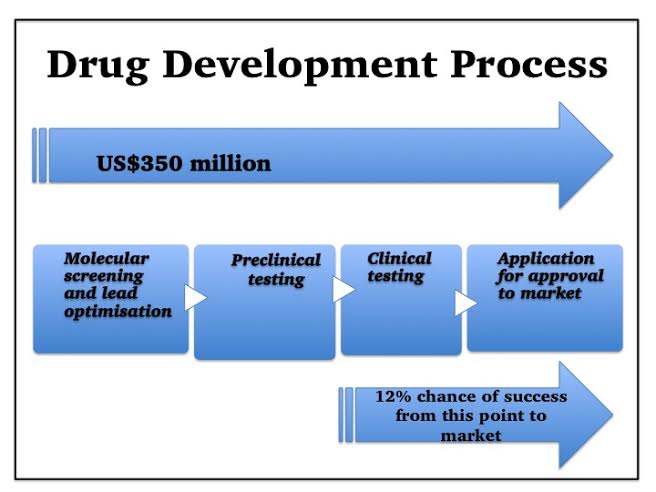

Let’s examine the drug development process.

First a drug target is chosen – often a protein molecule (receptor) on the surface of some of our cells.

Thousands of chemicals are then screened. If they bind to this receptor, they could influence how that cell works, and hence affect disease activity.

Chemicals which do bind are further narrowed down to those with additional potential drug properties—those likely to be well-absorbed, lack toxicity, and remain in the body long enough to work.

A lead candidate is chosen, and then modified further, optimising its chances of success.

Next, as required by government regulations, it is tested in animals and in the test-tube, for potential safety, effectiveness, and suitable dose.

Finally, clinical trials can begin. Often in healthy volunteers first, then small numbers of patients and finally in many patients. Thousands of people are usually tested before a drug can be marketed, and the size and duration of clinical trials has increased, as regulatory requirements have increased1.

Consequently, the typical cost of a new drug development is US$350 million according to a recent study by Forbes2.

But it’s worse than that—the development path is littered with booby-traps and precipices. Fledgling drugs frequently fail, and the Tufts Centre study found that, even those medicines which make it as far as clinical trials, have only approximately a 12% chance of eventually reaching the market3.

Thus, including the costs of failed developments, the actual cost for each successful drug is nearer US$2.6 billion3, and for many smaller companies, if the roulette wheel isn’t kind, the cost is failure and liquidation.

Pharmaceutical companies are not angels, nor are they demons. To survive, they must make enough profit from their marketed drugs to fund their development pipeline, in addition to returning some profit to shareholders. Long drug-development times, mean they may only have a few years of patent-protection left to achieve this. If governments force prices down, companies sometimes react by reducing development risk – choosing drugs more likely to succeed in preference to innovative but riskier developments for difficult diseases.

A typical drug development takes around ten years – so we won’t see this effect immediately, and when we do, it will be too late – it could take another ten years to correct.

So there’s the problem – health bills cannot continue rising exponentially, but forcing drug prices down has serious consequences too. What to do?

Further Information and References:

1. http://www.phrma.org/sites/default/files/pdf/rd_brochure_022307.pdf

3. http://csdd.tufts.edu/files/uploads/Tufts_CSDD_briefing_on_RD_cost_study_-_Nov_18,_2014..pdf

Note: These articles express personal views. No warranty is made as to the accuracy or completeness of information given and you should always consult a doctor if you need medical advice