When I was a child, eggs were definitely good for us – We were encouraged to ‘go to work on an egg’ and boiled eggs with runny yolks and toast soldiers were a healthy meal.

Then in the 1970s everything changed. We were warned that eggs raised blood cholesterol. This caused atherosclerotic plaques (fatty deposits), which narrowed our arteries and reduced blood flow, resulting in heart attacks and strokes.

Overnight the egg was recast from hero to villain.

These changes were based on some small studies of animals which were fed high-cholesterol diets, plus large trials involving people who regularly ate cholesterol-rich foods such as eggs.

Forty-years on, we understand that the conclusions reached were flawed.

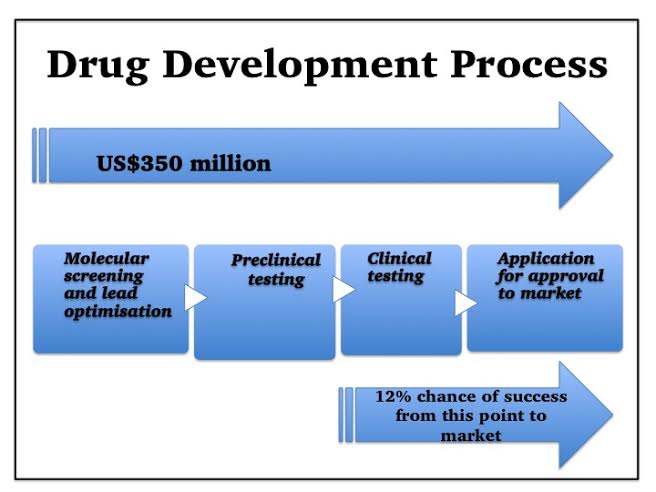

Dietary studies are always difficult. It is relatively easy to compare a group of patients who are given a new drug with a group who aren’t. In contrast, one can hardly make a group of people eat copious daily eggs for several years, to see whether they suffer more heart attacks than people who don’t.

So, usually people with a certain eating pattern of interest (eg high egg consumption) are followed, and their rates of disease are compared to those with different eating patterns.

However, confounding factors can influence these results. The people who ate lots of eggs in the cholesterol studies often also consumed more saturated fats and trans fats too, in red and processed meat. Other important factors which can affect blood cholesterol, such as physical activity and exercise, were also different between the two groups.

Consequently, eggs were wrongly blamed for blood cholesterol increases.

One should always be wary of facts based on research. Studies are very powerful tools, and numerous important advances have resulted, but the accuracy of data is dependent on the design of the study and interpretation of the results, and can be misleading.

The reality for cholesterol is more complicated than people thought. Our body makes most of our cholesterol itself. Food sources only contribute slightly in most people. Even then, eating eggs raises (protective) high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, rather than the harmful low density lipopoprotein (LDL) type.

Diabetics handle cholesterol differently, and some people are sensitive to cholesterol. These, in addition to people with familial hypercholesterolaemia (an inherited condition) may need to limit dietary intake.

For most though, blood cholesterol is best controlled with exercise, not smoking, weight control and avoiding saturated and trans fats.

Eggs are an excellent food source. Egg protein provides all the amino acids needed to build healthy muscle. The fat in eggs is mainly monosaturated (44%) and polysaturated (11%). They provide vitamin D and other important nutrients and a medium egg only contains 80 calories.

Free-range chickens can eat worms, insects and other natural foods, which could theoretically improve the quality of their eggs, but all eggs are good.

So, why not go to work on one?

Further Information and References:

http://www.bmj.com/content/346/bmj.e8539

http://www.webmd.com/heart-disease/guide/heart-disease-lower-cholesterol-risk

Note: These articles express personal views. No warranty is made as to the accuracy or completeness of information given and you should always consult a doctor if you need medical advice