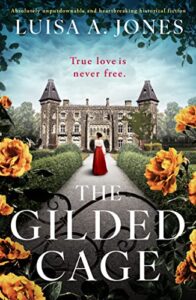

The Gilded Cage emphatically introduces Luisa A Jones as a fresh and modern voice in historical fiction. It’s hard-hitting, pulling no punches in the way it deals with the domestic violence that is at the heart of this Edwardian story, and the author doesn’t hold back when it comes to the love scenes either.

When Rosamund’s circumstances force her into marriage with Sir Lucien Fitznorton she is too young and innocent to even imagine the horrors that await, sharing her life with this controlling man. At the beginning of the story she is broken, with no allies, but that slowly begins to change when she uses Sir Lucien’s absence to learn to drive. Society and the servants consider her a little mad, but to her it represents a freedom she could never have imagined and she begins to recover at least a little confidence.

When Rosamund’s circumstances force her into marriage with Sir Lucien Fitznorton she is too young and innocent to even imagine the horrors that await, sharing her life with this controlling man. At the beginning of the story she is broken, with no allies, but that slowly begins to change when she uses Sir Lucien’s absence to learn to drive. Society and the servants consider her a little mad, but to her it represents a freedom she could never have imagined and she begins to recover at least a little confidence.

Although the story is a little slow to start, later it rattles along, its depiction of life in an Edwardian country house meticulously drawn, and by the end I was quite breathless to know what would happen.

What lingers most in the memory about this book are the brutally realistic depictions of the violence Rosamund has to suffer, particularly contrasted with the tenderness in some of the scenes which follow as she discovers her sexuality for the first time. I asked Luisa why she had chosen to write the book this way.

I was aware when approaching publishers for this book that certain aspects would be too strong for some readers, but I felt it was essential to tell Rosamund’s story honestly, and not to shrink away from depicting the harrowing impact of abuse. It was important to me to have her ultimately finding her own agency, and for her to experience tenderness and pleasure, despite her earlier dreadful experiences.

I was aware when approaching publishers for this book that certain aspects would be too strong for some readers, but I felt it was essential to tell Rosamund’s story honestly, and not to shrink away from depicting the harrowing impact of abuse. It was important to me to have her ultimately finding her own agency, and for her to experience tenderness and pleasure, despite her earlier dreadful experiences.

Rosamund’s story was inspired by several people I know well who have been raped and/or otherwise abused. I was, and always will be, incensed by the idea of anyone deliberately subjecting another person to sexual, mental or physical harm. A disturbingly high proportion of women report that they have experienced at least one incident of sexual assault in their lifetime. Rape within marriage was only made illegal in Britain under the Sexual Offences Act of 2003, and until at least the 1990s the law held that by marrying, a wife was effectively consenting to sex whenever her husband wanted it. Marital rape is still legal in many countries.

Alarmingly, a survey in 2018 by YouGov revealed that a third of British people believed non-consensual sex wasn’t rape if it didn’t involve violence, even though anyone with any understanding of psychology will tell you that freezing and flopping are common responses to threat, along with the perhaps more well-known responses of fight or flight. The same survey showed that a quarter of Britons believed non-consensual sex within marriage isn’t rape. I can’t read those statistics and not feel deeply angry.

I am aware that many will find aspects of Rosamund’s experience uncomfortable to read. If I upset any reader, I feel for them. Those scenes are included in the hope that her story will challenge people to rethink, and highlight that nobody should be used as another person’s sexual plaything. Everyone should have the right to decide who touches their body, whatever they wore when they went out for the evening, no matter whether they’ve flirted with the other person, and whether or not they once agreed to marry them.

Most of all, I hope I have honoured the real-life survivors I know and love, and that readers will not perceive Rosamund solely as a victim. I hope they will rejoice with her when she experiences kindness and feel uplifted at the end of the novel. For me, she is a victor.