If you imagine that finding a traditional publisher for a first-time unknown author is hard, think scaling the north face of the Eiger when it comes to LGBT writers. Equality has given us many opportunities in life, but in the world of publishing it has strangely reduced our chances. For while most publishing houses these days have LGBT authors and books on their catalogues, they are reluctant to take on too many and certainly when it comes to risky first-timers. Publishing, like any business, is driven by profit margins, and since gay authors and LGBT themed books are limited in their sales revenue, any manuscript landing on a publisher’s desk with a rainbow theme running through it, stands even less of a chance than the thousands of others already in the slush pile. Once, traditional publishers wouldn’t touch overtly LGBT books. Thus, it was left to independent presses to print small numbers, but which at least meant they were going into the shops, if only to be tucked away on a shelf at the back. Today, though the stigma of books dealing with a sexuality other than ‘the norm’ no longer holds sway, still the readership is relatively small and does not translate into big enough profits for the main influencers, the publishers who are supplying the highstreets and airport shops.

If you imagine that finding a traditional publisher for a first-time unknown author is hard, think scaling the north face of the Eiger when it comes to LGBT writers. Equality has given us many opportunities in life, but in the world of publishing it has strangely reduced our chances. For while most publishing houses these days have LGBT authors and books on their catalogues, they are reluctant to take on too many and certainly when it comes to risky first-timers. Publishing, like any business, is driven by profit margins, and since gay authors and LGBT themed books are limited in their sales revenue, any manuscript landing on a publisher’s desk with a rainbow theme running through it, stands even less of a chance than the thousands of others already in the slush pile. Once, traditional publishers wouldn’t touch overtly LGBT books. Thus, it was left to independent presses to print small numbers, but which at least meant they were going into the shops, if only to be tucked away on a shelf at the back. Today, though the stigma of books dealing with a sexuality other than ‘the norm’ no longer holds sway, still the readership is relatively small and does not translate into big enough profits for the main influencers, the publishers who are supplying the highstreets and airport shops.

What percentage of book sales are LGBT? I scoured the internet for information but could find nothing. Someone must have these figures?

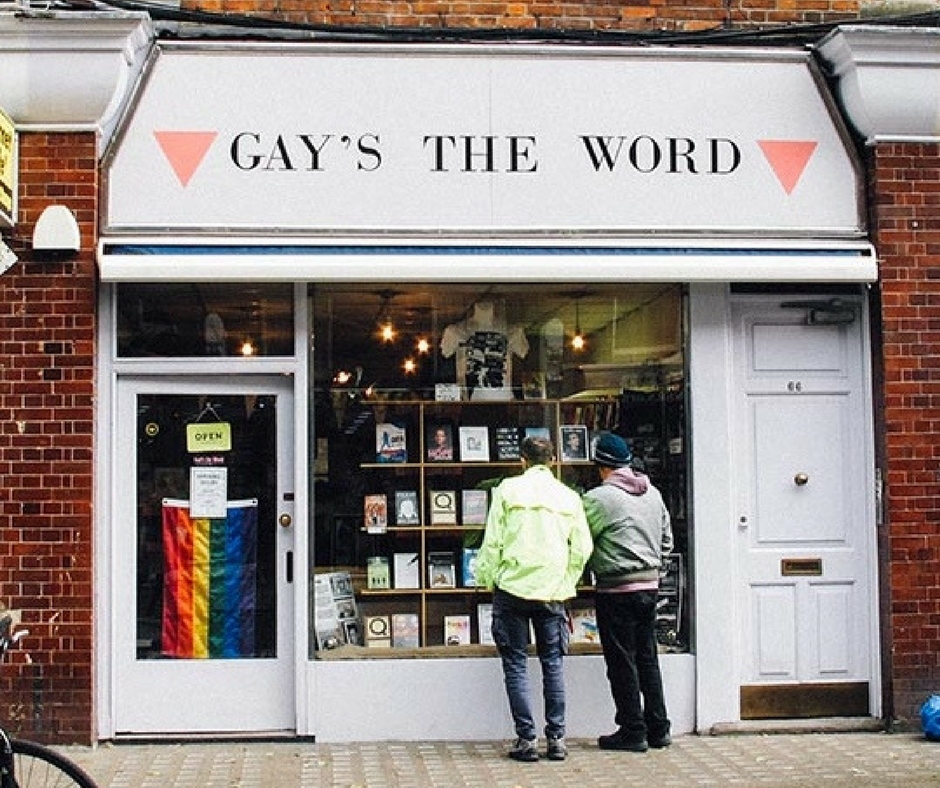

The scarcity LGBT bookshops seems also ironic, given the diversity we so enjoy today. There are only two in the UK (correct me if I’m wrong); Gay’s The Word in London, and Category Is Books in Glasgow. While LGBT only bookshelves are disappearing from the high street, independent bookshops such as the two mentioned provide much needed havens in which gay men and women can browse quietly and mix with other LGBT people. But why are there not more of these oases in our cities and towns? Are we missing something? Have we let the mainstream absorb so much of our culture that we are in danger of losing our identity and risk being ignored altogether? Is this what equality is?

Women in literature faced a similar dilemma when in 1992 a group of people from all areas of the literary world got together to discuss why The Booker Prize shortlist the previous year had not included any women writers. This was puzzling since 60% of books published were by women and yet they had been so underrepresented. The group discussed the value and purpose of literary prizes and whether they promoted reading or put people off, and the positive role such awards can bring to authors. From that meeting the Orange Prize for Fiction was launched in 1996. It is now called The Women’s Prize and is an important and integral event in the literary calendar.

Apart from the Polari Prize for first time LGBT authors and the Diva Literary Awards, the only other solely LGBT prize is the LAMDAs based in the U.S. While the acceptance of LGBT literature into the mainstream has given it just as much chance of winning any of the plethora of book awards, and is welcomed, the fact remains that the LGBT category will always be so small it will inevitably make little impact on the shortlists.

The Green Carnation Prize was initiated in 2010 when, together with journalist and blogger Simon Savidge, Paul Magrs highlighted this ‘scandalous lack of prizes for gay men’ in the UK. Since 2017 and despite its success, it has fallen dormant. If help is required, the gay community must assist in either resurrecting this prize or establishing another if we are to give gay authors and their books the attention they deserve. It will take the support of major players and sponsors for it to happen and to be sustainable, but as the Women’s Prize has proved, it can be done.