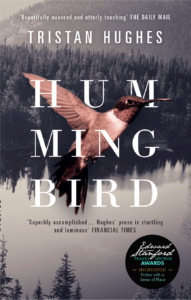

Hummingbird by Tristan Hughes is out now and is the winner of the Edward Stanford Travel Writing Awards 2018, in the category for Fiction, with a Sense of Place.

“What you could change and alter could never be finished or complete or dead. This is what I had been told back then, and what I had tried very hard to believe in since.”

Beside a lake in the northern Canadian wilderness, fifteen year old Zachary Tayler lives a lonely and isolated life with his father. His only neighbours are a leech trapper, an eccentric millionaire, and an expert in snow. But then one summer the enigmatic and shape-shifting Eva Spiller arrives in search of the remains of her parents and together they embark on a strange and disconcerting journey of discovery. Nothing at Sitting Down Lake is quite as it seems. The forest hides ruins and mysteries; the past can never be fully understood. And as Zach and Eva make their way through this haunted landscape, they move ever closer towards an acceptance of what in the end is lost and what can truly be found.

You beautifully evoke the Canadian wilderness in Hummingbird. I felt the need to reach for another sweater as I read it. Is Sitting Down Lake based on a real place or a blending of many?

The name is fictional, but it is based on a real place: a remote lake in the wilderness outside the small town of Atikokan (which appears as Crooked River in the novel) in northern Ontario. My grandparents had a log cabin there where we’d spend our summers as a family when I was child. It’s very much as it appears in the novel, with the bay and the islands and the railroad tracks. When my grandparents first went to the lake, there was no other way of reaching it except by canoe or by hitching a ride in the caboose of a passing train (there were no scheduled stops and only a few trains ever went by), although these days there’s a dirt logging road that takes you close. My family still has the cabin and I return there whenever I can. Oddly enough, I wrote the majority of Hummingbird in a rickety old fishing shack on another, relatively nearby, lake, and would often visit by road or boat (or across the ice by snowmobile in the winter).

The characters in the book reflect and reinforce the sense of place. To what extent do you think we are shaped by our surroundings?

I think places are a bit like pets sometimes – if we spend enough time in them, we begin to take on some of their characteristics. Also, we do tend to be drawn to – and to fall in love with – places that reflect us in some way, that speak to some part of our personality and perhaps magnify it. And it works the other way around too: we shape our surroundings by how we see them and how we imagine them. People overlay landscapes with stories and folklore, with songs and pictures, with their hopes and fears and desires, and all of that becomes part of the landscape too. It’s how we come to inhabit places and make them our homes.

The landscape is bleak and stark but imbued with its own beauty. Having lived in both Canada and Anglesey do you think the isolation afforded by such landscapes has shaped your writing?

In some ways I think it has. I’ve spent so much time immersed in those landscapes – with my hands in the dirt, so to speak – that they’ve become part of my creative DNA. They were also the landscapes of my childhood, and those places tend to have a special power or resonance for us. When I was young, they were my playground and my schoolroom; where I learnt how to see the world and how to imagine it. I was outside a lot, and quite often alone, and as I wandered around exploring I’d make up stories and the landscape was part of them. Looking back, I can see that these places have always been characters in my writing because they were ever-present characters in my life. And like the best characters, they have many layers; they are stark and rugged and beautiful, full of histories that lie just beneath the surface, predictable and then unpredictable by turns. I’m constantly discovering something new and surprising in what I thought was familiar, like in a long and successful love affair. And it’s not always easy either. My father is a farmer and growing up on a farm I learnt that the beauty of a landscape can be hard and tough and unforgiving sometimes; they are places of work as well as contemplation. And I also learnt that there was danger lurking in those landscapes: you could slip through the ice; you could go missing; you could freeze to death. And you had to respect that, because however much you love them they never really belong to you.

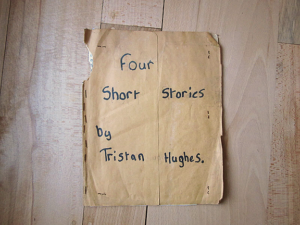

I understand that Hummingbird was inspired by a book you wrote when you were nine years old. Of the four short stories contained within it what made you revisit this particular story?

It was. About three years ago my mother was rummaging through the attic when she found what I guess was my first book. It was made up of twenty handwritten pages, clumsily stapled together between two pieces of cardboard, with the catchy title ‘Four Stories’. A mouse had eaten most of the top left corner. Most of the stories were about aliens taking over my primary school, and dinosaurs, and finding a chest of gold in a cave. But the last, and the longest, of them was about a man who walks into the wilderness of northern Canada and never returns. That one was based on a true story. About a hundred years ago, my great uncle wandered off into the forests of northern Ontario and didn’t come back. They never found a body. There was a set of footprints leading to the shore of a remote lake, and then … nothing. It was as though he had stepped off the face of the earth. Looking at those awkwardly scribbled pages, I could see how my nine-year-old self simply couldn’t comprehend that somebody could just disappear. The story must have haunted and bewildered me. There were no miraculous discoveries, no remarkable interventions from spaceships, no dream to wake up from. In some ways, the shakily handwritten words were an attempt to follow those footprints into a world I was too young to properly understand – a darker world of loss and grief.

After reading the story as an adult, I began to imagine a character living in this remote and lonely place, trying to deal with the sheer incomprehensibility of sudden loss, and it slowly began to turn into the novel. I think sometimes we are drawn back to those moments when we first realise something, even though we don’t yet quite understand it. And maybe that is where stories begin – as footsteps guiding us into the unknown.

There is much of the silent understanding between the male characters in the book and then along comes Eva who starts asking questions and talking about things. Do you think there is a clear difference between the way males and females deal with life events? Eva’s need to find answers and Zach’s acceptance of what he has been told?

In some ways Hummingbird is about the doomed efforts of the characters to submerge memory, to freeze time. They are trying to protect themselves from the past by not speaking about it, by attempting to insulate themselves in silence. But Eva brings a more active, questing energy to the community at Sitting Down Lake and begins to challenge that reticence. The novel is trying to ask what happens when the ice thaws? what exists beneath the snow? And Eva is the catalyst for this, the character who brings all these things to the surface. There is something about her bravery and forthrightness – her desire to confront the past – that offers the other characters a kind of redemption or route towards reconciliation, a way to properly face what they have tried to hide from. So, I don’t know if there is any intrinsic difference, but I would say that although Eva is the same age as Zach, I think in many ways she is much more mature than him. She is also less of a passive observer – she is not prepared to let things be.

Tristan Hughes was born in northern Ontario and brought up on the Welsh island of Ynys Mon. He is the author of three novels, Eye Lake, Revenant, and Send My Cold Bones Home, as well as a collection of short stories, The Tower. He is a winner of the Rhys Davies Short Story Prize and is currently a senior lecturer in Creative Writing at Cardiff University.